Talk about nutrition and female training means touching a sore button. There are different points of view on this: there is the faction that argues that women "must push like a man", the one who is in favor of differentiation and, finally, the one that differentiates so sharply by training the woman in such a bland way that no adaptation is verified ... therefore no improvement (except initial improvements, when you are new

A thing, however, is certain: managing a woman is more difficult.

- Weight loss is not linear and progressive

- The emotional sphere is widely involved in the choice of foods (sad --> sweet and soft/nervous --> crunchy)

- Many women live a special relationship with their bodies and food (even without ever completely leading to a DCA)

- They give a lot (too much) attention to the judgments and comments of those around them ("you were better before", "you lost too much weight", "you are getting too muscular", "I see you more swollen than a few months ago")

- They have a very delicate balance and a condition of chronic stress can lead to abnormalities that in humans are less evident and occur more in the long term (alteration of the adrenal hypothalamus-pituitary axis that almost always carries with it an alteration of the hypothalamus-pituitary gonad axis and alteration of thyroid function)

- athlete's triad

- risk of osteoporosis and changes in the menstrual cycle due to an inadequate diet.

in short.... women are more at risk of nutritional deficiencies and disorders related to CHRONIC stress.

What is the best programming for a woman is not the subject of this article, maybe we will talk about it in a later time. In this article we focus on the nutritional aspect and, in particular, nutrition able to support the requests of a athlete woman thus avoiding risks of malnutrition and visible consequences in the long term and difficult to recover.

Following a diet that does not meet energy and nutritional needs have a higher risk of:

- musculoskeletal lesions

- changes in the menstrual cycle

- hormonal imbalances (cortisol, DHEA, sex hormones, thyroid hormones)

- sideropenic anemia

- endotelial dysfunctions

- mood disorders and alterations

- deficit in the immune system

- poor sports performance

- low levels of perceived well-being.

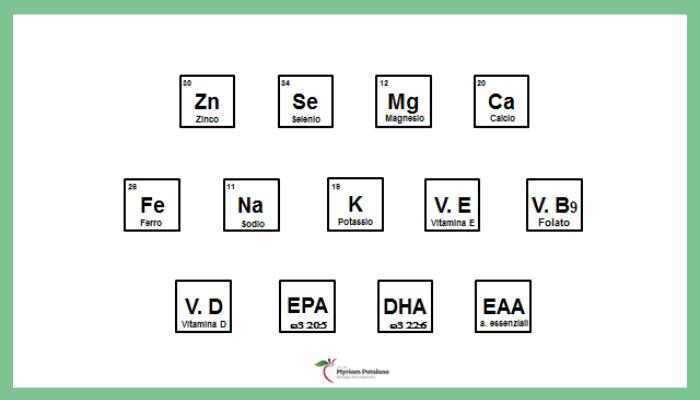

The risk is not only related to energy intake and macronutrients (carbohydrates, proteins, fats) but also and above all essential nutrients and micronutrients: essential fatty acids (EFA) including EPA and DHA (whose deficiency may result in increased systemic inflammation and oxidative stress), essential amino acids, calcium, vitamin D, B vitamins, folate, magnesium, iron, zinc, selenium etc...

Sports at risk

There are sports that present greater risks than others.

Low energy content and nutritional deficiencies are common in athletes who practice sports where it is important to pay attention to body weight. So sports, gravitaational and category of weight:

bodybuilding, powerlifting, boxing, triathlon, swimming, running, cycling, gymnastics, dance, skating, ski jumping, diving, light rowing.

In this type of sport, especially "aesthetic" ones such as bodybuilding, it is not uncommon to find eating disorders (DCA), from nervous anorexia to binge drinking and obsessive-compulsive disorders, thus also compromising the appearance mindset.

Some athletes do not voluntarily make restrictions but it can happen that they eat in a disordered way (poor food quality, preserved products, junk food) or it can happen that they exaggerate with the income of vegetable fiber such as fruits and vegetables associating this behavior with what is defined as "Healthy Lifestyle".

- High consumption of packaged, "ready-to-use" foods of poor quality carries the risk of a shortage of micronutrients in the diet and a condition of systemic inflammation.

- A high consumption of fruits and vegetables but also of whole grains can slow down gastric emptying, increase the sense of satiety and unconsciously affect the daily intake. Not only that! An abuse of fiber (soluble and insoluble) can lead to intestinal discomforts that negatively affect performance: meteorism, constipation, swelling, heaviness, disbiosis.

Sometimes it is the exercise itself (when it is very taxing) that affects appetite, especially in conditions of chronic stress.

An adequate diet, which supports macro and micronutrient needs, and support through specific integration greatly help to:

- reduce the risk of injury (maximising athletic performance and resilience)

- minimizing the risk of disease (supporting the immune system)

- minimize the risk of the athlete's triad.

As for the last point (the triade of the athlete) it is a medical syndrome characterized by psycho-physical disorders and a poor state of health of the female athlete. It is a syndrome NOT ALWAYS to be linked to disorder of eating behavior.

A decade ago, low energy income was identified as a risk factor in the triad of the female athlete contributing to slow bone mineral density (BMD, which can lead to osteoporosis) and monstrual disabling (irregular cycles, anovulators, hypothalamic amenorrhea).

Menstrual disabling may occur due to suppressed levels of leptin that interrupt the signaling cascade for estrogen and progesterone synthesis. In particular, low levels of leptin impair the pulsatility of the hormone releasing gonadotropin (GnRH) leading to a reduced secretion of the luteinizing hormone (LH) from the pituitary and finally to reduce gonadic production of estrogen and progesterone.

The net result is a menstrual interruption that occurs along a continuum from mild (e.g. anovulation or deficiencies of the luteal phase) to serious irregularities (e.g. oligomenorrhea (cycles ≥ 35-40 days) that can progress in amenorrhea (no menstruation for > 90 days).

Another reason for menstrual disorders may be the theft of PREGNOLONE, typical consequence of chronic stress.

Pregnolone is the common precursor sexual hormones and cortisol.

In chronic stress, the demand for cortisol increases, subtracting a large part of pregnolone; the body considers survival to be primary, less priority fertility and, therefore, reduces (or stops) the production of sex hormones.

The consequence is a hormonal imbalance that affects the menstrual cycle.

It is not just a question of fertility, of whether or not we want to have a child: it is a question of health.

In athletes with menstrual dysfunction or actual amenorrhea, low BMD (low bone density) has been observed, increased risk of osteoporosis and what are called stress fractures.

That's why it is so important managing stress in a woman, proper programming and correct nutrition... because the alteration of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis also drags with it an alteration of the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonad axis.

Symptoms of excessive stress

- Excessive hair loss

- Brittle hair and nails

- Insomnia or night awakenings

- Waking fatigue

- Chronic fatigue and poor resilience

- Altered resting heart rate

- Variations (even small) in the menstrual cycle

- Abnormal body temperature

- Digestive problems

How much and how should a woman who does sports at certain levels eat?

There are women who eat, deliberately or unconsciously, between 800 and 1000 kcal/day.

In these conditions of metabolic crash not only performance and health are compromised but, in the event that there is a need for a cut or weight cut to fall into the category or to obtain certain "aesthetic" details, this cannot be done (in these conditions what is cut?!).

In such a condition it is convenient to act with a metabolic reset going to intervene both from a nutritional point of view and from a training point of view. During the reset phase, a particularly important role is assumed by the glucides which, among many things, allow us to regain vigor and metabolic inefficiency (at 800 kcal / day the body becomes extremely efficient, a bit like that of the obese where everything that is introduced is used, there is no waste as it happens, instead, in naturally thin subjects).

How long should this reset last?

The answer is, of course, very subjective but, in a generic way, a female athlete should get to support *at least* 34 kcal per kg of lean mass, 0.8 g of fat per kg of lean mass, 4 g of carbohydrates per kg of lean mass.

So the bare minimum for a woman who does sports at a high level is:

- Introth: 34 kcal/kgMM

- Fat: 0.7-0.8 g/kgMM

- Carbohydrates: 4 g/kgMM

From these numbers, then, you can safely improve even more. We need to think about the long term, support the well-being and physiology of the athlete and make sure that, once we get to the period of weight cutting, there is room to be able to cut.

Each one, then, has its own metabolic parameters (based on genetics, nervous system, hypothalamic function, body biotype). To establish the best energy needs for *that athlete* in particular it is important to have a correct food history, evaluate the type of physical activity (and the type of stimuli supported) and lifestyle (recall, food diary, see the woman in person while training).

A recent study in 2018 talks about:

- 25-35 kcal/kg with 3-5 g/kg in fitness-taking people (1 hour for 3-5 times a week)

- 45-70 kca/kg with 5-8 g/kg carbohydrates in athletes who train up to 3 hours 4-6 times a week

- very high income with 8-10 g/kg of carbohydrates in elite athletes with a very active lifestyle.

In "naturally thin" women you do not have to rely on appetite to manage caloric intakes: they are women who, usually, have little hunger, difficulty in taking high doses of "clean" food, difficulty putting on weight.

If there are problems of this type, you should not be afraid to include "refined" foods, snacks, foods with high energy density (many calories in a small volume), vitargo, maltodextrins, cyclodextrins etc ...

They are athletes, so they have good insulin sensitivity. Do not be afraid to "dirty" the diet!

In the event that the problem is the difficulty in reaching certain doses of proteins, essential amino acids (EAA) can be exploited, preferably in capsules or single-dose sachets (best stoichiometric ratio).

Calorie restriction phase

When does the restriction phase arrive?

A rapid drop in weight due to a drastic cut at the last moment negatively impacts muscle mass, the nervous system and performance. Not only that! A drastic cut will result in a rebound post-race (rapid weight gain after the competition) and, this increase, is mainly borne by liquids and fat mass.

For the weight cutting it is important to start early, invest in the OFF season without, however, getting too far from the category weight, planning in advance what will be, then, the competitive season so that you can lose weight slowly and gradually, preserving muscle mass, performance and health of the athlete.

To preserve the health, the hormonal balance of the athlete and minimize all risk factors (even in those stages of preparation considered more "extreme" as a definition or fall into the pre-race weight category), it is important to take into account some "rules":

- monthly weight loss of around 1.5% of body weight

- correct hydro-electrolyte balance

- never delete the sale

- do not go down with the intake below 24-25 kca/kg of lean mass

- do not go down with grasses below 0.5-0.6 g/kg of lean mass

- training contextualized according to the phase and the income of the period

- when things do not go as planned Never force your hand, rather reschedule your competitive season.

Both the quantity and quality of macronutrient intakes are important to support the health and performance of athletes.

It is important that the sports nutritionist interacts with the sports doctor and the athletic trainer (also with the psychiatrist if he is present in the team).

Teamwork is the key!

Bibliography

- Venkatraman JT, Leddy J, Pendergast D. Dietary fats and immune status in athletes: clinical implications. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(7 Suppl): S389–95

- Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Meyer, N.L.; Lohman, T.G.; Ackland, T.R.; Maughan, R.J.; Stewart, A.D.; Muller, W. How to minimise the health risks to athletes who compete in weight-sensitive sports review and position statement on behalf of the Ad Hoc Research Working Group on Body Composition, Health and Performance, under the auspices of the IOC Medical Commission. Br. J. Sports Med. 2013.

- Manore, M.M.; Kam, L.C.; Loucks, A.B. The female athlete triad: Components, nutrition issues, and health consequences. J. Sports Sci. 2007

- Mountjoy, M.; Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Burke, L.; Carter, S.; Constantini, N.; Lebrun, C.; Meyer, N.; Sherman, R.; Steffen, K.; Budgett, R.; et al. The IOC consensus statement: Beyond the Female Athlete Triad—Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S). Br. J. Sports Med. 2014

- Thomas, D.T.; Erdman, K.A.; Burke, L.M. Position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics, dietitians of canada, and the american college of sports medicine: Nutrition and athletic performance. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016

- Horvath, P.J.; Eagen, C.K.; Fisher, N.M.; Leddy, J.J.; Pendergast, D.R. The effects of varying dietary fat on performance and metabolism in trained male and female runners. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2000

- Barrack, M.T.; Ackerman, K.E.; Gibbs, J.C. Update on the female athlete triad. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet Med. 2013

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D and Calcium. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D; Ross, A.C., Talor, C.L., Yaktine, A.L., Del Valle, H.B., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011

- Márquez, S.; Molinero, O. Energy availability, menstrual dysfunction and bone health in sports: An overview of the female athlete triad. Nutr. Hosp. 2013

Dott.ssa Patalano Myriam Biologist Nutritionist

Ischia Nutrizione Patalano